Much content on this site supports all three communication mediums: text, video, and audio

Much content on this site is offered across all three communication mediums: text, video, and audio. As to text, there is the written content on webpages, of course, but once I add videos, you can also view the written content broken out into presentation slides.

It is my hope that these slides may be a great help to those who wish to use the materials of this site in their own Bible teaching endeavors – while the materials of this site are copyrighted, as long as proper attribution is given, they may be used in all non-commercial endeavors without any other strings attached. (The limiting to non-commercial endeavors is because I am against making money off of the teaching of the Word of God, as a general principle). So here, you can freely teach through any of the slideshow presentations yourself, as long you don’t pass them off as your own, but instead say something to the effect of “I didn’t make these – they came from BibleDocs” and give a link to the site.

As to videos, they primarily live on this ministry’s YouTube channel.

There will always tend to be at least some text content that is not yet backed by video and audio

The order in which content is filled out is always text ➜ video/audio; that is, at any given point in time, there will almost certainly be some written studies on the site that I have not yet recorded the videos for. Making the videos and then subsequently making the timestamps/transcripts is not terribly complicated, but it does take some time and effort.

Once I have checked-over and polished some content, I may be comfortable releasing it on the site (in written form) before I really feel like it is the right time for me to make the video for it. It may prove to be useful to people in written form long before I might be able to get around to making the video, so why wouldn’t I let people make use of it in this intervening period?

Nonetheless, supporting video and audio is important to me too, and I see a lot of value in it, so over time, most content will eventually end up actually supporting all three content mediums.

Sometimes when building out larger studies, I find it helpful to have more down on paper before I completely finalize the sequencing of things. This is not a strict rule I follow, but it does occasionally turn out this way.

Thus, when I am working on a longer piece, video production may lag even more behind than normal. At least sometimes.

Why go through the effort to support all three communication mediums?

This is because:

- Some people tend to generally learn better via one specific medium, and this can differ by individual. (It is especially important from an accessibility standpoint: dyslexia, blindness, and deafness all pose no issue if you support all three mediums).

- Even for the same individual, different mediums can be better at different times. For example, if you are cooking dinner or working out at the gym, it might be difficult to read a text study, but listening to an audio version of it might work.

In general, text specifically is good when you are searching for something, if you want to read back a bit to situate where you are (that is, you find yourself getting lost in the discussion and want to refresh yourself on the context), and/or if you want to compare different parts of a study side-by-side. Put differently, text has certain advantages in serious study that the other mediums simply cannot match, and is for that reason irreplaceable, in my estimation.

Other than these considerations, however, you can go with whichever medium works best for you. I recommend mixing and matching based upon circumstances. (So, for example, text and videos when you have time to sit down and focus, and maybe audio when you are multitasking with other things but still want to listen to the studies).

Content supporting all three communication mediums has many facets

There are a great many things that go into the organization of content that spans across all three communication mediums:

- A descriptive title

- A link to the video playlist for the wider study the content is a part of

- A link to see the full slides of the presentation

- A concise summary of the topics the content discusses

- Full timestamps by topic (these apply to both the video and the audio)

- The text of the slides laid out without divisions, to be able to read through it seamlessly, navigate via a dynamic table of contents, and search or skim through it without having to go slide-by-slide

- The full written transcript of the spoken content, hyperlinked statement-by-statement to the video

Content types

While most all content on this site is structurally similar in that it follows the pattern above of supporting all three content mediums, it is organized into different sections on top of this. At present, this site has four content types:

Shorter topical studies

The Shorter Topical Studies on this site go over things topically (tracing a subject rather than sticking with a specific part of scripture), and tend to trace topics much narrower in overall scope than those covered in the Longer Topical Studies, which is why they end up shorter.

Longer topical studies

The Longer Topical Studies on this site go over things topically (tracing a subject rather than sticking with a specific part of scripture), and tend to trace topics much wider in overall scope than those covered in the Shorter Topical Studies, which is why they end up longer.

Verse-by-verse studies

The Verse-by-verse Studies on this site go over things one verse at a time (sticking with a specific part of scripture rather than tracing a subject). I have adopted the practice of covering verses as I feel led to, which means that in addition to going through entire books of the Bible in order, sometimes the verse-by-verse content on this site will tend to be more scattershot, tackling some difficult verses here and there across many different books. Over time, of course, I hope to have the coverage and continuity increase.

Not every single thing written in these verse-by-verse studies on the site will have a video made about it, but only the things of sufficient length and complexity to merit such. This means that there will be a number of shorter notes that will only show up as text on the study webpages (which are organized by chapter).

Q&As

The Q&As on this site are dedicated to treatments of various topics, organized in a question and answer format. Some of these Q&As come from correspondence with site readers, while others (both questions and answers) are completely of my own creation.

The “answers” contained herein are not necessarily to be taken as holy and unquestionable writ (after all, they are coming from myself, an imperfect human being), but simply as responses to the questions.

Page types

Content types cluster content based on its primary area of focus (as in brief treatments of specific topics vs. verse-by-verse notes on the text of the Bible, for example). Dividing the content along these groupings makes good sense, to make sure that all similar content ends up listed in the same place.

Within each content type, webpages can be further categorized into three hierarchical layers, by page type. On top, we have list pages, which list out all the studies within a content type by title and summary. Clicking on one of these on the list page will take you to the aggregation page for that study, which contains the aggregation of content pages in the study, all strung together in the same place for easier skimming and searching. You can click on a top-level header on the aggregation page to be taken to the corresponding content page, if you want to read sequentially (one block of content at a time) rather than skim through or search through everything altogether.

Speaking by manner of rough analogy, list pages are like library indices (giving you titles and summaries to pick between books on a shelf), aggregation pages are like books (a collection of chapters strung together), and content pages are like individual chapters.

If all this still seems too abstract, you’ll find that you’ll have no problems using it in practice. It’s very intuitive.

List pages

Pages of this type list out all studies within a content type by title and summary. If you view the organization of pages as a pyramid-like tree, list pages are on the narrow, top part of the pyramid.

This site has list pages for all of the content types that go by subject/topic rather than passage:

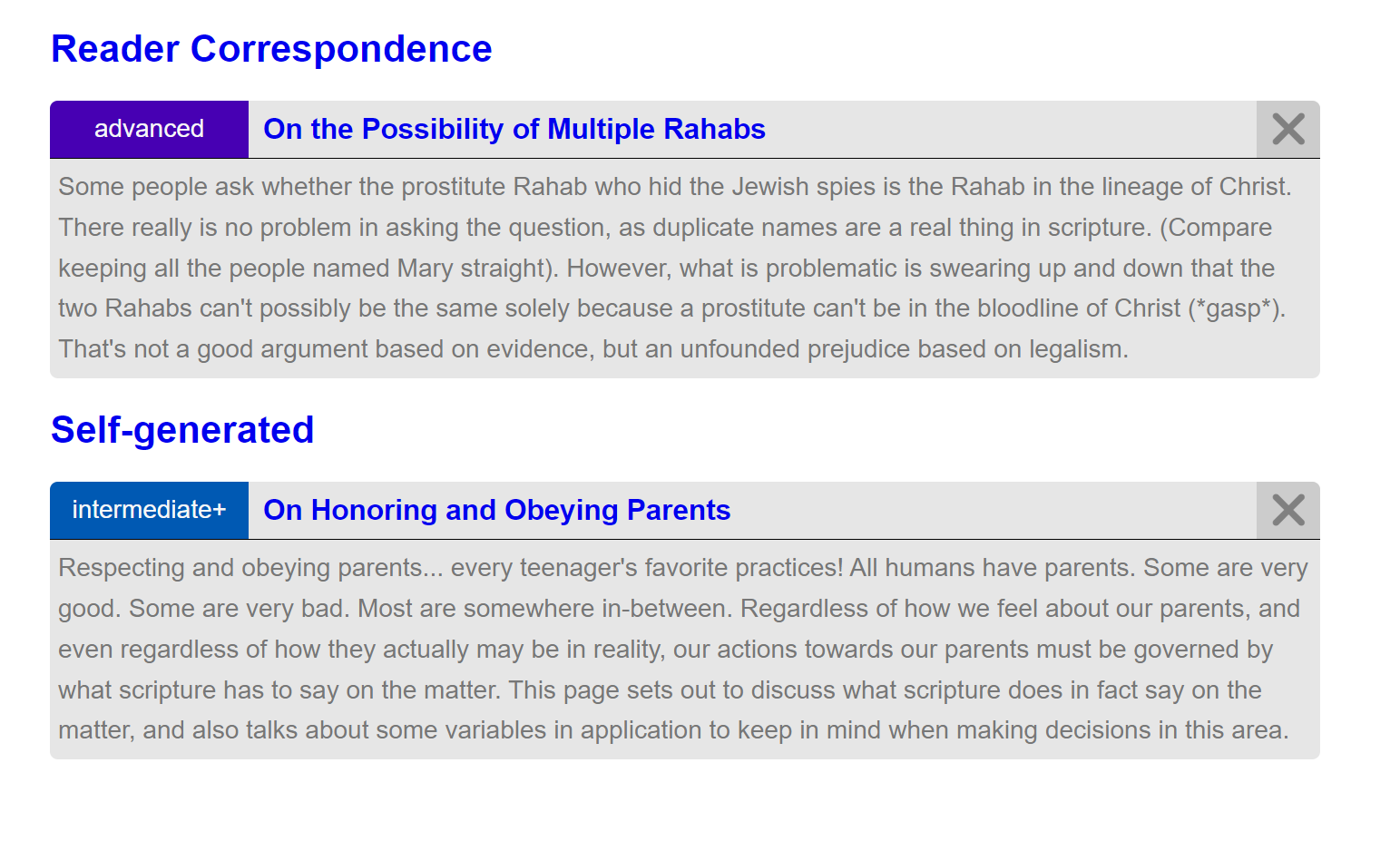

List pages have a list of studies with titles and summaries. Something like this

Toggling summaries on list pages

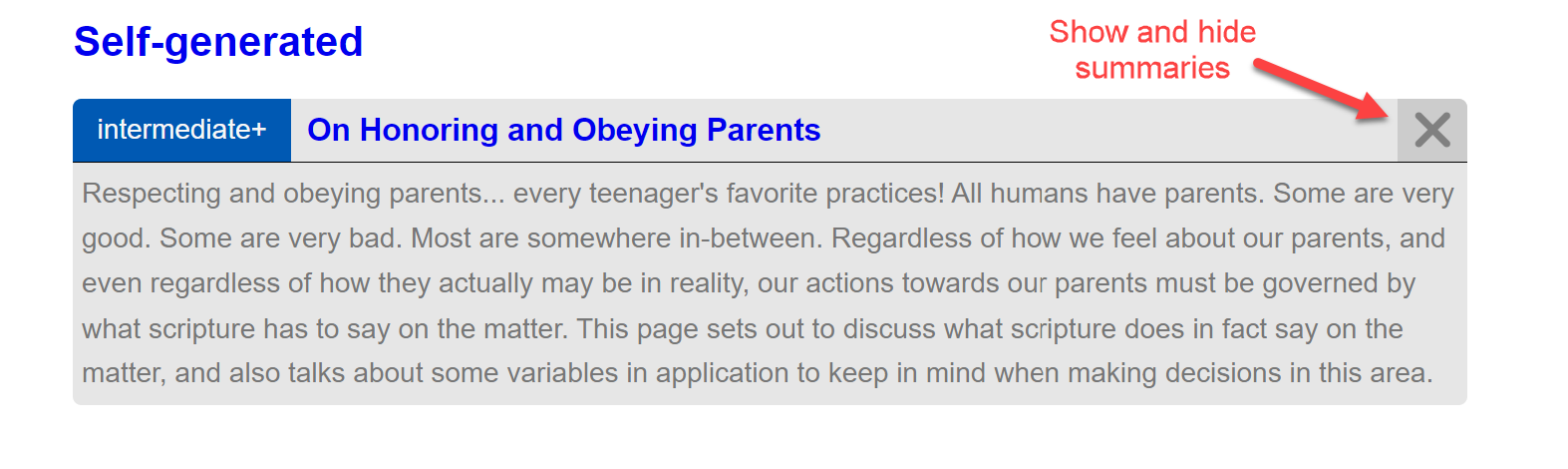

On these pages, you can choose to either show or hide the summaries for the content when viewing the lists. If you choose to hide the summaries, you will just see the titles. If you choose to show the summaries, you will see both the titles and the summaries.

You can toggle the summary visibility individually for each thing in the list (using the + or x in the top right corner of the list item):

You can individually toggle summary visibility with the button in the top right corner

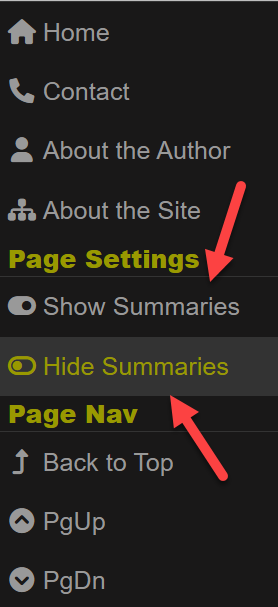

You can also do it on a per-page level, or even set a default setting to persist across the entire site. To toggle the summary visibility for all the studies on one of these list pages, you can select one of the appropriate options in the sidebar menu:

The sidebar menu options for toggling the display of summaries

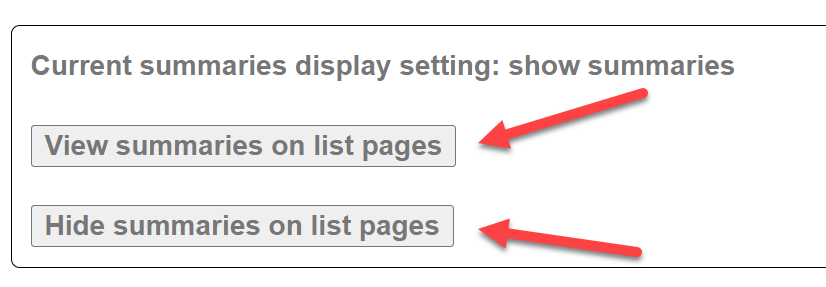

To set whether or not summaries are shown or hidden by default across the entire site, you can make the appropriate selection on the settings page:

The site setting for toggling the display of summaries

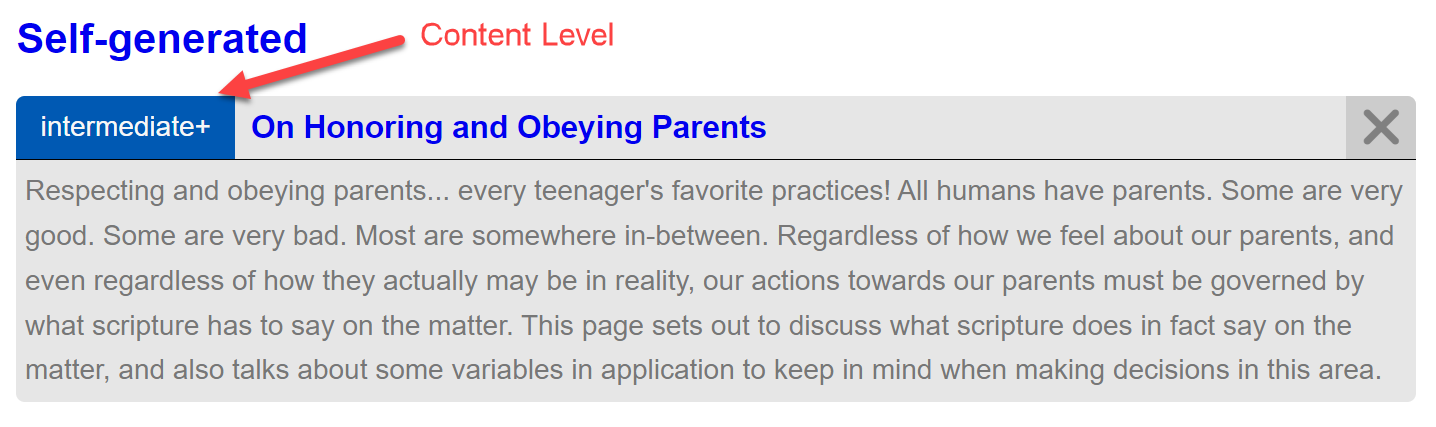

Content level labels

Each study listed on a list page has a content level (the colored label over on the left). You can read more about content levels below.

Each study has a corresponding colored content level

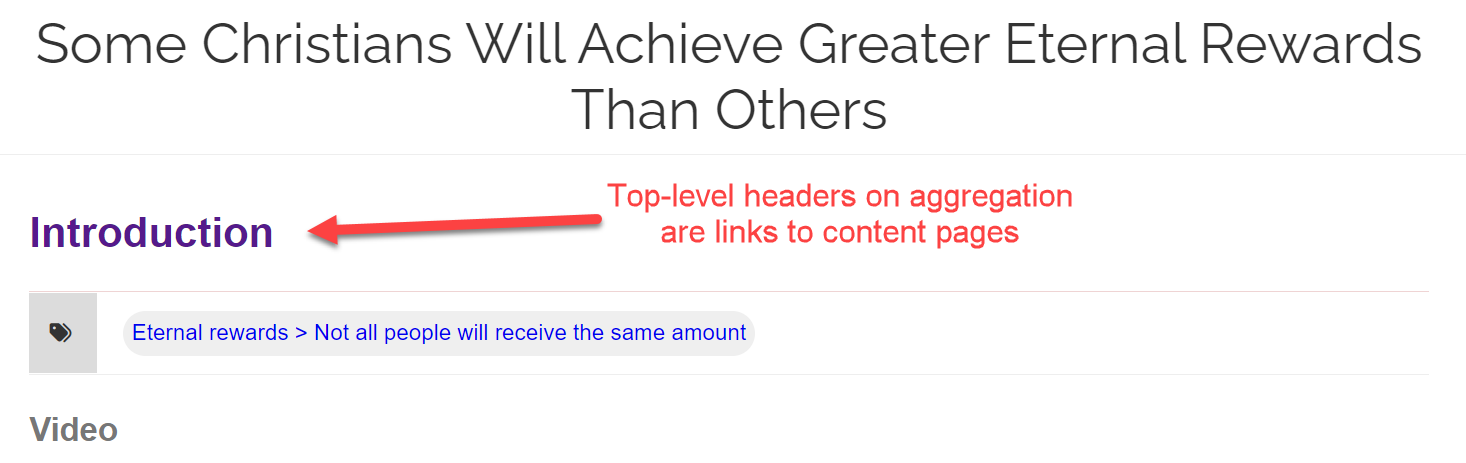

Aggregation pages

Pages of this type aggregate all content within a study in the same place (that is, on a single page) to make skimming and searching easier. If you view the organization of pages as a pyramid-like tree, aggregation pages are in the middle of the pyramid. This means there are far more aggregation pages = distinct studies than there are content types (the things on the narrower top part of the pyramid), but far fewer aggregation pages than content pages (the things on the wider bottom part of the pyramid), since each aggregation page is composed of many content pages stuck together.

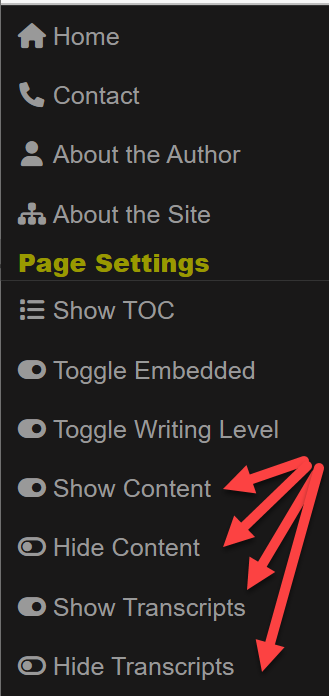

On aggregation pages, content sections and transcript sections can be toggled to show or hide their contents. By default, they hide their contents. This is so because content sections and transcript sections are by far the longest and least useful sections for skimming (relative to summaries and timestamps, which give you far more information at a glance).

Clickable headers: navigating to content pages

Top-level headers on aggregation pages are links to each respective content page in the study. If you click on one of these links, you will be taken to the actual content page, where you can start reading sequentially (one block of content at a time) rather than skimming through or searching through everything altogether.

Top-level headers on aggregation pages are links to content pages

Toggling content and transcript sections on aggregation pages

You can toggle each content or transcript section individually by clicking on it (try it below). Note that the sections are dynamically added to the TOC when shown, and removed when hidden.

Content

This is some content that can be shown and hidden

Video/audio transcript

This is a transcript that can be shown and hidden

You can also toggle the visibility of all content sections or transcript sections at the same time through links in the sidebar menu:

You can show or hide all the content sections or transcript sections on an aggregation page through the sidebar menu

Content pages

Pages of this type contain a neatly-boxed treatment of a topic – the content related to a single slice of the pie. There may be many content pages in any given wider study, grouped together on aggregation pages for easy searching and skimming (see above). If you view the organization of pages as a pyramid-like tree, content pages are on the wide, bottom part of the pyramid.

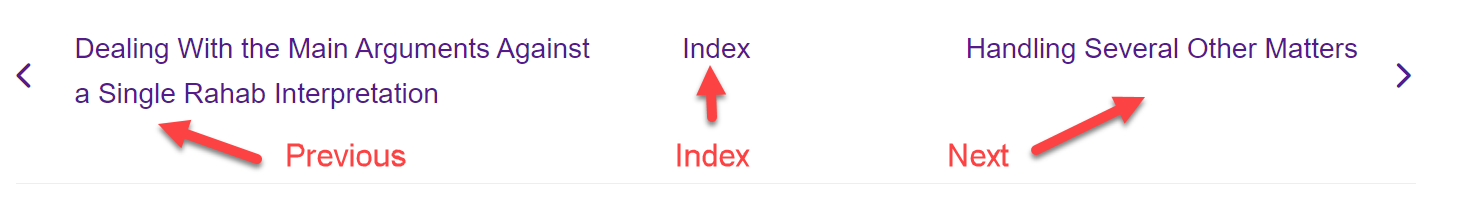

Because content pages individually only compose part of a wider study, it is often the case that you might want to move around from one page to another within the same study. For example, you might want to move one page forward or backward in the study, or perhaps jump back to the aggregation page to search or skim through all the content in the study.

Study navigation at the top and bottom of each content page

At the top and bottom of each page is a simple navigation section containing a link to the study’s aggregation page (the middle link titled “Index”), and then links to the Next/Previous content pages in the study – as appropriate (the last page in a study won’t have a Next link, for example).

The study navigation at the top and bottom of content pages will look something like this

Study navigation in the sidebar menu of each content page

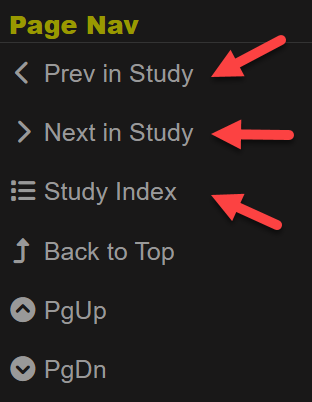

For convenience, these same links show up in the sidebar menu as well, in the “Page Nav” section. This means that no matter where you are on the page in terms of scrolling, study navigation will only ever be a single click away.

You can also navigate within a study using links in the sidebar menu.

Should I primarily read on content pages or aggregation pages? How about searching? How about skimming?

If you are planning to sit down and take in a full study (look over all the content from beginning to end, thoroughly), I would suggest going through the content pages one by one, using the study navigation to go from one content page to the next, in order.

This is because the table of contents for each individual page will be smaller and easier to scan at a glance, and each section stays nicely focused and boxed. This structure also lends itself well to enabling organization via consistent study patterns, like going through one content page a day, for example.

For searching and skimming, however, that is where the aggregation pages shine. You can quickly skim an entire study, and then uncollapse a content section and/or transcript if the topic catches your eye. Or search for a phrase across all study content, and so on. So for searching and skimming, I do very much recommend making use of the aggregation pages, as that is what they were designed for.

Content level

Just like essentially all other pursuits in life, spiritual knowledge builds on itself progressively, with advanced topics only really becoming understandable once more fundamental ones are understood. (Although there are differences that set spiritual knowledge apart, to be sure: we have the all-important help of the Holy Spirit in quickening our understanding, and even more than head knowledge, actually believing and applying that which we are learning is critical in spiritual growth).

Anyhow, content on this site is labeled as to its overall spiritual difficulty level (compare Hebrews 5:12-14), as it seems to me, in order to help newer believers sort through where it might be wise for them to start. This sort of labeling is subjective and hand-wavy, it is true, but hopefully it can be at least somewhat useful as a guide. The labeling looks like so:

- basic

- basic+

- intermediate

- intermediate+

- advanced

- advanced+

- mixed

The distinction between the bare labels and the “plus versions” (e.g., basic and basic+) is the “ease of acceptability / controversy factor” – things with plus labels are more controversial and/or harder to accept, as it seems to me. It so happens that many of the things that are controversial and/or harder to accept are more advanced teachings, as one might expect. Christians disagree about the basic parameters of the gospel very little, but particulars of eschatological chronology quite a bit, for example.

The main reason why I only define and use three content levels is because the lines are so blurry and indistinct. I would be quite uncomfortable breaking things down any more, since fine-grained categorizations would really imply a level of precision that simply isn’t there.

Part of this is because different people find different things hard (i.e., my intermediate might be your basic), so any labels I affix are really my best guesses as to how “most Christians” will relate to the content. The same goes for my decisions about what content gets the plus distinction and what content does not.

I should emphasize that all the content is for everyone. One never outgrows revisiting basic spiritual teachings, in other words.

Just for example, we all need to be reminded that we are sinners in need of redemption, God’s enemies by nature, and entirely undeserving of the blessings that we have been given. That Jesus Christ – fully God, yet fully man – came and died for us as a perfect living sacrifice, so that we might be reconciled to God. That He laid down His life and bore our sins upon the cross in order that we might be saved from the consequences of our sinfulness. Not that we deserved it, but that God, out of His boundless grace and mercy, saw fit to send His one and only Son and judge Him in our place.

All this to say, these labels are not supposed to be mutually exclusive from the perspective of the reader, as if once you think you can handle intermediate teachings, all the basic topics are somehow unworthy of your attention. The idea is instead to help give a rough sequence to things for newer believers who need to start somewhere, so that they might not be quite so overwhelmed. At least, that’s the idea.

Writing level

For this site, content level measures “spiritual difficulty level,” while writing level measures how difficult the writing is for someone to read. If you have heard the term “reading level” (e.g., “her daughter reads at a 4th grade reading level”), then you are on the right track. The Lexile system is one formal implementation of the concept.

I personally think using the term “reading level” for written content is confusing – reading level is a property of human readers, not writing. I have thus opted to use the term “writing level” to denote the level at which content is written.

For example, let’s say an article has a 9th grade writing level. Alice reads at a 11th grade reading level, so probably wouldn’t have problems reading the article. Bob reads at an 8th grade reading level, and could probably read the article if he took his time and looked up words he didn’t know (and so on). Charlie reads at a 5th grade reading level, and would probably find the article too difficult.

Put simply, this site tries to write at as low a writing level as possible at all times. I will be the very first to admit that, despite this goal, not all writing on this site ends up at a particularly low level. While I find it a very worthy goal, it is very difficult to realize consistently due to the paradoxical fact that it takes more time and effort to properly control one’s writing such that the same content is presented in a way that is shorter and simpler rather than longer and more unbound in complexity.1

For me specifically, it also doesn’t help that I was forced to do a lot of scholarly writing in the many formal essays I had to write as part of my two humanities majors in college, so my “default mode” is very dense academic prose. Apologies.

The next sections will, respectively, outline exactly what writing at a low level means, why such a practice is useful, and then finally the mechanics involved in toggling between the two writing levels this site employs.

What is involved in a low writing level?

It is a combination of things, but the biggest contributors are probably:

- Reduced overall length

- Simpler sentence structure

- Simpler vocabulary

- A vastly reduced use of idioms – which are often unnecessary to convey specific meaning, but can make writing completely incomprehensible to people unfamiliar with them

- A vastly reduced use of foreign loanwords and borrowed phrases (e.g., c’est la vie, sine qua non, etc.)

- A vastly reduced use of complex or fanciful simile, metaphor, metonymy, and so on – things that some readers may be unfamiliar with (just as with idioms)

Why would we want a low writing level to begin with?

The simplest way to explain this is to consider the fact that while advanced readers can read writing written at a higher or lower level, some people will only be able to handle writing at the lower level. What’s the best way to maximize the usefulness of your writing across all people, then? To always write a lower level.

By my reckoning, there are three big groups that benefit most from lower-level writing:

- Children

- Non-native English speakers

- Folks without as much education

Children do not yet have fully developed reading capabilities; there is no way around this. Many children (particularly young boys) also have an incorrigible aversion to sitting still for long periods of time. You have to settle for shorter lessons with them, or suffer the consequences of irritated, cooped-up child. (Some children are exceptions, but not many).

Non-native English speakers (particularly those at the more rudimentary stages of language acquisition) have a hard time with complex writing for obvious reasons. English is a difficult foreign language to learn in part because of its huge vocabulary, so it is a good start to not lean on variation in vocabulary so much, even if doing such is considered inferior stylistically. Simpler sentence structure also makes it much easier to keep up with subjects and verbs and relative clauses and so on, which also helps foreign readers. But by far the kindest thing you can do for foreign readers is simply to make writing convey as much information as possible in as concise a way as possible. Fewer sentences to struggle through to get the information is a great blessing for struggling readers.

In fact, the exact same general principles hold for helping all those native English speakers who also struggle with more advanced writing. I have noticed an exceptionally harmful form of intellectual snobbishness in certain Christian circles (not that there isn’t a place for scholasticism and academic rigor among Christians – perish the thought!). It would do us well to consider that many people end up without substantial education not because they were lazy or undisciplined, but because of circumstances largely out of their control. God puts all of us in different places, after all. The Bible itself makes the point all over the place that worldly status is nothing before God, who holds the very strings of the universe in His palm. All that matters in His eyes is the right spiritual attitude. We should thus make sure as Christians that we always seek the best outcome for the Church as a whole (“the big picture”) rather than just focusing on the well-dressed suburbanites before us. (Not that there is anything wrong with well-dressed suburbanites, mind you. They just do not represent the sum totality of the body of Christ here in the world).

In any case, the better I am able to wrangle my writing into some semblance of “simple and concise,” the better it is able to serve these three groups who would otherwise not be able to make use of it (or at least not nearly so well). And that is a most excellent goal entirely worthy of pursuit. Even if it makes me personally look less educated or refined or whatever.

The toggle between higher-level and lower-level writing on this site

I just spent quite some ink arguing for the practice of always trying to write in as accessible a way as possible. Now I’m talking about higher-level writing? What gives?

Good question. Note the comparatives. We are discussing “higher” level writing not “high” level writing. In fact, the vast majority of the content between the higher and lower level versions of writing on this site is exactly the same – written as simply as possible, as just described.

The higher-level writing is in fact higher in writing level because:

- It is longer due to having tangential discussion in the text

- It is longer due to having technical discussion (e.g., of Greek and Hebrew) in the text

- The writing in the technical discussion sections tends to be more complex due to its subject matter

- The scripture quotations in it are all from normal translations not as targeted at simplicity (e.g., the NIV84, ESV, NASB, NKJV)

Or, if you wish to look at things from the reverse direction, the lower-level writing is in fact lower in writing level because:

- It is shorter due to eliminating tangential discussion in the text

- It is shorter due to eliminating technical discussion (e.g., of Greek and Hebrew) in the text

- It does not have the more complex writing of the technical discussion sections

- The scripture quotations in it are all from a translation targeted at simplicity (the NIrV)

And there you have it. I hide two of the special content sections in the lower-level writing (sidenotes, technical discussion) and use the version of the NIV written at approximately a third grade writing level (the NIrV), making the writing shorter and simpler overall, and therefore easier to read. However, if you can handle a bit of added length and added complexity in your Bible version, the higher-level writing will give you a bit more of a nuanced view of things.

It is worth pointing out that even in the sidenotes and technical discussion sections in the higher-level writing, I still try to keep the writing as simple as possible. That is to say, I don’t switch into full-blown academic mode as soon as a Greek word comes up, for example, but still try to keep everything as accessible as possible, even if the subject matter itself is inherently more complex.

Special content sections

I take pains to mark out various sections in the writing on this site, according to the contents they contain. There are two big reasons for this practice:

- Marking out the content sections makes explicit boundaries between types of content. For example, being completely clear in distinguishing teaching from application is important for ensuring that people don’t become dogmatic about things that the Bible does not actually teach as global absolutes (i.e., become dogmatic about things that should be specific to only their particular circumstances).

- Marking out the content sections makes it very easy to skim writings to find content of a specific type or to avoid content of a specific type when reading. For example, if someone is interested in reading mostly about application, they can look for green sections in the text and quickly skim over the rest. If someone doesn’t have a technical background and wants to skip technical discussion (involving matters of Greek, Hebrew, analysis of scholarly positions, and so forth), they can simply scroll through orange sections in the text.

Text that does not fall into any of the content sections (i.e., text without any special background color) should generally be taken to be Bible teaching with direct support from scripture.

You can see examples of each of the content sections below, with Lorem Ipsum text in place of actual content. In the wild, these content sections may end up being quite a bit longer, even containing multiple headers and sub-headers.

Note that special content sections can be nested inside of each other, even several layers deep. For example, there might be a technical discussion section that contains a sidenote section that contains a quote section. Since all sections have different background colors, with a bit of extra styling (to leave some extra padding), this nesting works quite nicely.

Cautionary notes

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Content falling into these sections is of two primary types:

- Warnings against false teaching

- Warnings against traps and pitfalls in application

Whether or not you read these sections (and/or how much time you spend seriously considering them) should naturally depend some on your overall level of spiritual maturity. Once a certain level of maturity is obtained, we are inherently more resistant to being blown off course by things that are false (see Ephesians 4:14-16), and also have more spiritual discernment to help us better grasp the general character of what we ought to be about (Romans 12:2). However, it never hurts to get a degree of exposure and inoculation to dangers in false teaching and problematic application, so that when you encounter them in the wild, they don’t take you off-guard. (The principle is much the same here as with vaccines in medicine).

The false teaching under consideration runs the full spectrum, from almost blindingly obvious things (“Give me money for my private yacht and God will bless you!”) to the much more subtle.

The traps and pitfalls in application also vary in nuance, ranging from “No, honoring your parents does not mean you should help them deal drugs” to less simple matters more like “Sometimes it can be a mistake to be too specific in the advice you give to impressionable new believers as they may come to rely on your word more than their own developing spiritual discernment, which can cause problems for both you and especially them down the road.”

Some people might protest that application is inherently an individual matter (see application special content sections, below) – given this, how can you dogmatically call some paths of application out as wrong? Perhaps the best way to answer this is by analogy. In college, I had a Greek professor who often liked to remind us (particularly after tests!) that “Just because there are many correct translations does not mean that there are not incorrect ones.” The same idea holds here. While we often cannot be dogmatic about what someone else definitely should do, we can be dogmatic about some things they definitely shouldn’t do.

Technical discussion

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

As described above in the section on writing level, the higher-level writing on this site sometimes contains technical discussion that is not included in the lower-level writing version of the same content. In general, the purpose of this discussion is to formally justify points made without toning things down so completely that the real matters themselves are not handled. This is not to say that discussions that fall into this special content section are made purposefully impenetrable or anything like that, but simply that the discussion is not nearly as tempered for an audience with less knowledge.

The upshot of this for most people is that you can probably safely ignore these sections unless you are interested in the full treatment. I am careful to include summaries of the main points of technical discussion sections in the normal text (as appropriate), making these sections completely optional. This means, for example, that if you skip one, I won’t suddenly reference something from it further down on the page.

The exact topics covered in technical discussion sections can vary, but the main idea is that they are focused on things that lay Christians really need not worry about understanding fully unless they have particular interest. A non-exhaustive list of things that can show up in technical discussion sections:

- Analysis, critique, and comparison of scholarly viewpoints on various matters.

- Many things relating to Greek and Hebrew

- Many things relating to textual criticism

- Many things relating to more advanced topics in hermeneutics

- Many things relating to more complicated facets of biblical archeology

- Etc.

Sidenotes

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Sidenote sections contain exactly what you’d think they would: writing that is only sorta-kinda related to what is under current discussion.

As a general principle, I try to avoid remarks that are well and truly off-topic, so these sections contain things that are related but only tangentially so.

These sidenote sections and footnotes are used somewhat interchangeably, although I probably use these more overall since they can be quickly scanned/skimmed visually whereas footnotes cannot.

Just like technical discussion sections, these sidenote sections are hidden in lower-level writing, for the reasons described above in the section on writing level.

Application

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

These discussions of application in the application sections are noteworthy relative to other content on this site since they are the only writings that contain things other than direct exposition from scripture. This is because application is very much an individual matter.

Each of us has a unique combination of spiritual gifts given to us at salvation (not to mention our own inborn talents and aptitudes, things also coming ultimately from the hand of God), along with personal experiences that have shaped us over many years, and a collection of present circumstances limiting the sample space of workable choices before us. Put simply, each of us is unique with unique circumstances, so what is right for me may not be right for you, and vice versa.

Of course, some things in scripture are completely black and white (e.g., “flee porneia”); these are not areas of application. On the whole, however, these black-and-white matters only compose a small fraction of the total number of things facing us each and every day. For this reason, it is vitally important that Christians learn to hone their own spiritual discernment and learn to listen to the still, small voice of the Holy Spirit in their hearts.

The content of these application sections

Writing in these special application sections does not set out to prescribe but to describe; rather than coming to conclusions, individual application sections instead focus on examining potential personal circumstances, and how different factors therein might be relevant. In other words, time is spent identifying possible variables in application.

Now, when making a decision, “weighing” variables is important: this one matters for me a lot, this one matters for me not so much, and so forth. This site avoids weighing variables in any fine-grained way (and thus avoids mapping out any actual possible routes of application) simply because these things are personal, and will necessarily vary by individual. (To be clear, they may still vary by individual even when everyone is doing exactly what God wants them to do – because God calls all of us to different things).

We need to be relying first and foremost on the guidance of the Holy Spirit to get things right, but this does not mean that we cannot or should not also utilize more systematic methods like those described here (analyzing problems, outlining variables, and making evidence-based decisions).

Ours is a God of the impossible, and faith is a muscle that must be exercised

One final caveat regarding application is that while it is reasonable and appropriate to make a habit of “doing our homework” when making decisions (as in the more systematized process with variables and so on above), it is important that we not wed ourselves only to practical considerations, for ours is a God of the impossible. For example:

- Moses, God’s chosen representative to appeal to Pharaoh to free the Israelites from Egypt, was not at all a good public speaker (Exodus 4:10, Exodus 6:12, Exodus 6:30-7:2).

- David, still relatively young at the time, was the one to defeat Goliath, rather than a seasoned military veteran.

- Peter, a fisherman without apparent educational credentials (compare Acts 4:13), became a very important leader in the early Church. (Compare his commanding influence in Acts 2).

In all these cases, “logic” would demand a different outcome than what was ordained in the (perfect and singular) Will of God. Yet these men, even against all odds, succeeded in doing what God would have them do, because they looked at their situations with eyes of faith. Their example should not be lost on us.

Faith is a muscle that must be exercised. Sometimes God sends tests our way that are more or less along the lines of choosing to believe His testimony (as found in the Bible) over what our eyes may see and our ears may hear. Our systematic analysis may tell us to do one thing, for example, while we perhaps instead feel led to do something that ranks quite poorly in that analysis.

The line to walk here is appreciating the importance of faith in our decisions (and taking great pains to not be closed to paths that require us to trust God and not have everything perfectly figured out) while not at the same time inherently valuing decisions that require lots of faith, as if they were somehow better on account of them being more impractical and unrealistic. In other words, while sometimes stepping out against seemingly impossible odds is exercising godly faith (so we should never truly count most paths of application out, even if they seem unworkable from our material perspective), sometimes doing such is also just foolish. Knowing the one from the other is why application is hard, and requires spiritual growth to the point of maturity.

General notes

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Unlike cautionary notes – which are warnings of some form – general notes are just as they sound: something to pay attention to a bit more.

Oftentimes I will put somewhat random information in these sections, things that don’t fit into the body of the text too well, but still need to be conveyed.

If you are familiar with the Latin abbreviation n.b. standing for nota bene (meaning “note well”), this is that same general concept, but instead of using an introductory abbreviation, we use a separate content section.

Indirect reasoning

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

This site employs two types of indirect reasoning: indirect reasoning that uses principles from scripture (more common by far), and arguments from probability.

Because the exact nature of the content contained in these sections is somewhat difficult to explain, there is a lot of writing below. You’ll forgive me, I hope. It seemed to me that being precise was more important than brevity, in this particular case.

Indirect reasoning that uses scripture

Bible teaching should focus on the Bible

Bible teaching done properly does account for matters relating to the historical transmission of the Biblical text – dealing with an academic discipline known as philology – as well as matters of ancient history and culture, archeology, and a few other things that cannot be established from the text alone. (See the following section on arguments from probability).

Nonetheless, it is not incorrect to say that in the vast majority of cases, good Bible teaching’s defining feature is its almost-singular focus on the Word of God. However, this does not mean that all teaching can necessarily point to specific verses that directly prove the point at hand.

Example: Hard drugs

For example, the Bible says nothing directly about recreationally doing heroin, a harmful street opioid drug (contrast morphine as used in a controlled way in medical contexts), or cocaine. However, the Bible clearly states that we are to submit to government authority (Romans 13:1-7, 1 Peter 2:13-17). If the government makes these drugs illegal, then it becomes wrong for Christians to do them, even though the Bible never specifically calls it out as wrong. Additionally, since being drunk and being under the influence of such drugs are similar in the important loss-of-conscious-control aspect, all the verses condemning drunkenness can also be indirectly applied to the practice of taking these drugs.

In this way, we we can dogmatically come down against these hard drugs (in shades of complete black and white), even though heroin and cocaine (and so on) did not even exist at the time the Bible was written.

Example: Arranged marriage

As another example, consider the question of arranged marriage. While not common in Western society, there are still areas in the world where it is more the norm than not (such as some places in India). Yet, some parties want to legalistically ban the practice of arranged marriage for all people. There is no verse in scripture along the lines of “there is no problem with arranged marriage” (that is, a verse directly relevant to the topic at hand); however, we have plenty of examples of it in scripture without any negative comment (e.g., Isaac and Rebecca). So, using indirect reasoning, we can still dogmatically say that there is no inherent problem with arranged marriage, even though the Bible doesn’t say such directly. We ought not be at all wishy-washy about it, since we do in fact have enough indirect evidence from scripture to come to black-and-white conclusions.

Why bother marking this kind of teaching out as different?

Keep in mind that this kind of teaching is different from opinion and conjecture. Bible teachers have a responsibility to teach the truth (which is objective and absolute), not personal opinions. No, what is under discussion here is not conjecture, but conclusions that are reached somewhat indirectly from reasoning based on direct scripture.

So why bother marking it out, rather than having all teaching presented as fundamentally the same? For one thing, while we as Christians can still be confident in indirect arguments from scripture if we go about the process the right way, by their very nature, there are more “things to go wrong” – it is easier to mess things up in indirect arguments, simply because there are more steps between the interpretation in question and scripture. When the Bible says something directly, it’s pretty hard to get things wrong, but when you have to string together a more complex argument to get from A to B, it is possible for imperfect human logic to yield incorrect conclusions.

In this way, marking out indirect arguments from scripture can signal to readers “you ought to check this section a bit more closely to make sure you see how the conclusions are ultimately traceable to direct scripture.”

Arguments from probability

Arguments from probability are another kind of indirect reasoning that deserve special mention. Generally, these arguments are not deductive in nature, but inductive. This means that they don’t mesh particularly well with the black-and-white approach to truth characteristic of formal Bible teaching, and generally shouldn’t be employed unless there is no other good choice.

What do I mean by “no other good choice?”

Most of the time a topic can be discussed in terms of scripture, even if indirectly, as just discussed above. As yet another example, consider that while the Bible doesn’t actually explicitly talk about a specific kind of named sin relating to cruel physical torture of others, it is not hard to come up with an airtight argument against it from scripture. Ever read Matthew 7:12?

However, occasionally there are topics that cannot be addressed (or at least not fully) using only internal evidence from scripture. Much of the time these topics aren’t important enough to even talk about. (Hence why the Bible, in its limited space, doesn’t bother addressing them).

Still though, in a small number of instances, there are topics that we need to take a hard stand on, but don’t have any good arguments – even indirect ones – from scripture itself. Many of these topics are related to textual criticism, archeology, and historical analysis.

These are the sort of cases where arguments from probability come into play.

Example: No, Matthew was not initially written in Hebrew

A good example of an appropriate use of an argument from probability can be seen in the debate surrounding the false notion that the gospel of Matthew was originally written in Hebrew (e.g., see here). There is essentially no way to disprove such a notion with scripture itself, but we do want to strongly shut down any claims like this that challenge the trustworthiness of the Biblical text, as being able to confidently trust in the Bible is absolutely critical for lay Christians. In this case, without any scriptural evidence we can turn to, our best weapon against this dangerous false position is an argument from probability.

If Matthew were in fact originally written in Hebrew, we would expect to have multiple mentions of this very important fact (given that the New Testament is exclusively written in Greek, were Matthew to be written in Hebrew, it would be very noteworthy) in early Christian writings. However, we don’t. Based on everything we know textually, the gospel of Matthew shows up overwhelmingly in Greek (and quite early too – e.g., in some of the earliest papyri we have), and while Hebrew copies of Matthew do eventually appear, they are late translations intended for evangelism among Jewish populations.

Moreover, if all the Greek copies of Matthew were translations from a Hebrew original, we would expect a great deal of variation in the Greek text. (Compare the textual tradition of the Septuagint – it is really appropriate to ask the question “which Septuagint?” since translation inherently introduces so much instability in the text). However, we do not at all observe this. There is variation in the different exemplars of Matthew we have (as is normal in hand-copied ancient texts), but it is not markedly different from the variation found in, for example, Mark or Luke (the other two synoptic gospels).

People who push for Matthew being written originally in Hebrew might make an argument along the lines of “Matthew was originally written in Hebrew, but it was translated into Greek very early, and only copies of this one single early Greek translation (rather than copies of multiple Greek translations from the Hebrew original) happened to get preserved due to historical happenstance, and therefore even early Christian writers didn’t know this important secret” (or something along these lines). Again, while we have no direct scriptural evidence we can use to refute such a claim, the argument from probability we have made above shines light on what this claim really is: complete and utter rubbish.

Conclusions regarding arguments from probability and indirect reasoning generally

Arguments from probability comprise another weapon in our arsenal, another tool in our toolbox. Most of the time when we mention “indirect reasoning” in the context of Bible teaching, we are referring to the practice of using the principles scripture teaches to weigh in on things it doesn’t address directly. Every once in a while, however, “indirect reasoning” can refer to the practice of using arguments from probability relating to things like textual criticism, archeology, and historical analysis (somewhat imprecise inductive scholarly practices) to take a hard stand on some point that we are unable to talk about nearly at all in terms of scripture itself.

In terms of these arguments from probability, as long as we only lean on them when appropriate, they can be a positive boon, helping us present ourselves to God as craftsmen unashamed, cutting straight the Word of Truth (2 Timothy 2:15). In the same way actual craftsmen always use the right tools for the job (not trying to pound in nails with screwdrivers, e.g.), so too should we as Christians.

Examples

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Perhaps the most self-explanatory of all the special content sections, example sections contain, well, examples.

Typically, examples are given in-line (that is, within the body of the text itself), but if they get kind of long, then I’ll pull them out and stick them in these sections.

Post hoc notes

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

These can show up in Reader Correspondence Q&As.

The phrase “post hoc” essentially means “after the fact.” The problem with updating writing from past exchanges transparently is that the reader is never made aware that changes were made since the exchange (so the posting party could unfairly rewrite the history of what was actually said – or something along those lines). But as long as I clearly set apart all information added to the initial conversation in post hoc notes, then no one can get the wrong idea about things.

Some notes may be added in-line [Post hoc note: this is an in-line note], while others may be too long for this, so that they are instead contained in these set-apart sections.

Quotes

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

I find that quoting text in larger blocks (even multiple paragraphs) is often useful. While many formatting procedures indent block-quotes, this ends up wasting a lot of space over the long-term (especially for long quotes). Changing the background color while otherwise leaving the styling the same is the most practical way to handle longer quotes, and that is exactly what is done here – just as with all the other special content sections.

The source for a given quote is linked in the label of the section (“Quote from {Source}”) in almost all cases. (The only real exception is when the source is not linkable for some reason, such as if a website no longer exists).

Scripture quotations

For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.

Scripture quotations are very similar to general quotes, but nonetheless are broken out into their own sections, to mark them out separately. For each section, the biblical passage being quoted shows up in the header, as well as the Bible version being quoted from.

Unlike the other special context sections, scripture sections do not have a different background color, but instead use a border. They are the only special content section to do this. This is because scripture sections, like quotes, frequently show up in all the other special content sections, so we want them to look good when nested = no matter what the color of the parent section is (since all the other special content sections use different background colors). Quotes look good when nested in all the other special content sections since they are silver (which doesn’t clash with any of the other colors), but “transparent with a border” is what I decided looked best aside from silver.

Original translations

So now that we have been justified by faith, let us take hold of the peace [we have] with God [the Father] through our Lord Jesus Christ.

Sometimes I decide to translate from the Greek and Hebrew myself instead of using established translations. These are the original translations on this site.

Original translations are a special subset of scripture quotations, so share the same styling. Just like scripture quotation sections, for each original translation section, the biblical passage being quoted shows up in the header.

Inferred words are added to the text using square brackets. These words do not appear in the original text, but are added by me to make things more clear. The King James Version does something similar, but added words in the KJV are italicized instead of using brackets. The main difference in what I do versus what the KJV does is frequency – I generally add many more words than does the KJV. The goal is to make the meaning of the text as clear as possible.

In addition to inferred words, I also make use of explanatory remarks in parentheses. To avoid ambiguity with parenthetical statements that are part of the actual text, all of the explanatory remarks I add begin with abbreviations, while I will never translate words that are part of the actual text with abbreviations. Here’s the full list of abbreviations that can introduce my explanatory remarks:

- i.e.: coming from Latin id est, meaning “that is.” The abbreviation I most frequently use, i.e. is used to clarify and explain.

- e.g.: coming from Latin exempli gratia, meaning “for example.” This abbreviation, unsurprisingly, is used to introduce examples.

- cf.: coming from Latin confer/conferatur, meaning “compare.” This abbreviation is used to introduce things that ought to be compared (or possibly contrasted) with the present topic. On this site, it is overwhelming used to introduce scripture passages as cross references: “Salvation comes by grace through faith (cf. Ephesians 2:8-9).”

- lit.: an abbreviated form of the English word literally. I use this abbreviation to give an additional more literal translation of a specific word or phrase. Used especially if the literal meaning is somewhat idiomatic in nature – which would be why the normal (non-parenthetical) translation doesn’t use the literal meaning. This is not something that only happens when translating Greek and Hebrew, by the way, as if these ancient languages were somehow unique in having specialized idioms. For example, you might consider the Chinese idiom 鶴立雞群. If I were translating a sentence with this phrase, perhaps it would go something like “Within his studies at University, John was an exceptional person among his peers (lit. “a crane standing in a flock of chickens”).”

Ichthys translations

(1) But now marshal your [own] troops (gdd, גדד), O city (lit., “daughter”) of troops (gedhudh, גדוד) [which are marshaled against you]. For they have laid siege to us. For they have struck on the cheek with a rod the Judge of Israel. (2) But you, O Bethlehem Ephrathah, too small to be numbered among the clans of Judah, from you I will bring forth the One who is to rule over Israel. His goings forth are from long ago, even from the days of eternity. (3) For He will give them over [to the oppressor] until the time when [Jerusalem] labors [like] a woman in labor. At that time the rest of His brethren will return to the sons of Israel (i.e., prior to the Second Advent). (4) For He (i.e., our Lord Jesus at His return) will arise and will be their Shepherd, in the might of the Lord, and in the majesty of the Name of the Lord His God. And they (i.e., His flock) will abide, for then He will be great, even to the ends of the earth. (5) For this One will be our Peace.

Sometimes I decide to quote from places where Ichthys translates directly from the Greek and Hebrew instead of using established translations. These are the Ichthys translations on this site.

Ichthys translations are a special subset of scripture quotations, so share the same styling. Just like scripture quotation sections, for each Ichthys translation section, the biblical passage being quoted shows up in the header.

Ichthys follows a similar syntax as myself (see just above) in adding inferred words and explanatory remarks in translation (although my practice is modeled on Ichthys’ practice, not the other way around).

-

You might compare the famous quote “If I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter.” It really is true. ↩︎