Introduction

The interface for this site is unapologetically geeky in what it sets out to do. I spent many months researching, designing, and testing functionality, even coding a good bit myself since I wasn’t particularly happy with any of the off-the-shelf options available to me.

Now, however, I am pretty happy with the results and overall user experience. While I am of course quite biased, I really do feel like this site offers quite a bit more useful content functionality than most sites out there – and by several orders of magnitude at that.

I do recommend reading this page pretty thoroughly if you wish to take advantage of all this site has to offer. There may be a bit of a learning curve, but some of the neat things you can do probably won’t completely make sense until you do.

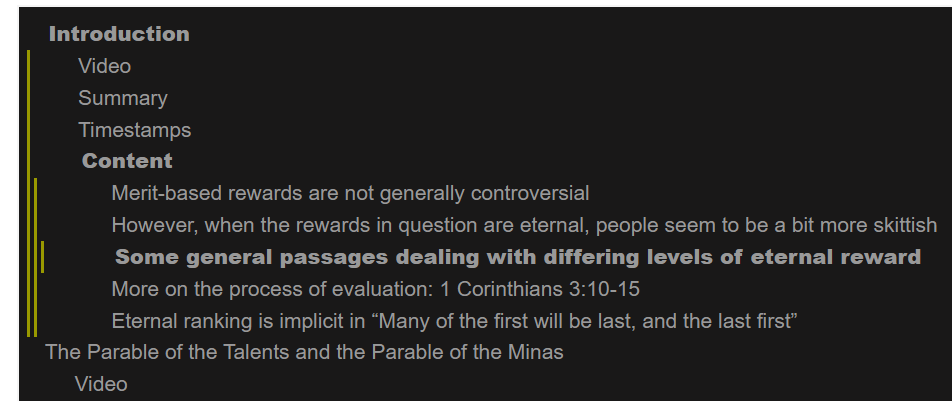

Dynamic auto-scrolling tables of contents

Every content page has a table of contents that updates dynamically based on where you scroll, actively flagging the most relevant information at any given point in time to make it more visible and make it clear at a glance where you are on the page:

- All active sections in the hierarchy will be bolded

- Gold lines on the left of the table of contents give a further visual indication of position, including section nesting

Note the bolded sections and the gold lines

Clicking on a link in the table of contents will immediately take you to that section on the page. After using such a TOC link, you can then copy the URL in your browser’s address bar to save a link to that page section (that you can then share with others, for example).

Subject index

It is very common for websites to support content categorization of some kind: adding categories or tags to pages to group things by topic. The problem with leaving things at just this is that it doesn’t work very well once pages get the least bit long, as it does not let you set up links that target specific sections (as in smaller blocks of content, such as several paragraphs), but only the whole page. This can lead to frustrating searching whenever you click on a link to a page tagged with a specific tag, as you look for the one part of the page that actually talks about the topic.

This has always struck me as silly. Why not have the link just go directly to the relevant section actually talking about the topic, rather than the whole page? It is not like there is any technical consideration making this unworkable, but it just doesn’t seem to be very common on other sites. Mysteries of the universe?

In any case, this site’s subject index uses this sort of superior targeted linking to link directly to relevant content, rather than being stuck with not-very-precise page-level content categorization.

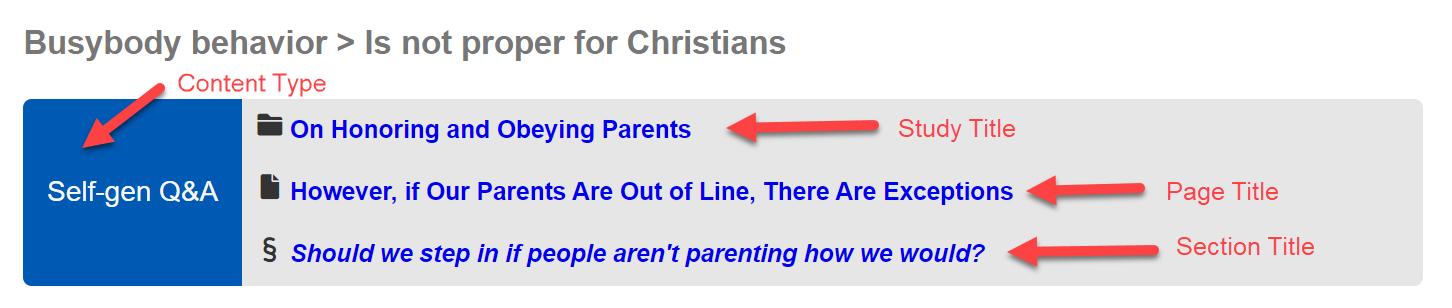

The structure of links in the subject index

An example subject index link.

Each link in the subject index contains as much contextual information as possible. Most links will link directly to specific page sections, so will have four important bits of information:

- Over on the left is a colored label denoting the content type of the page that is being linked to. (For example, perhaps someone may only want to see Q&A discussion of some topic, rather than teaching in a verse-by-verse context).

- In the text section of the link, the top line (with a folder icon) represents the title of the study within the content type that is being referenced (each content type contains multiple different studies, each of which will contain multiple pages = lessons).

- In the text section of the link, the middle line (with a page icon) represents the title of the page within the study that is being referenced (each study contains multiple different pages, each of which will contain multiple different sections = headers)

- In the text section of the link, the bottom line (with a section icon) represents the title of the section within the page that is being referenced (the text of that specific section’s header – this will be the same as the text displayed in the TOC link for that section).

Some links will actually link to pages as whole (these are less common, by number). These links will still have items (1) through (3), but since they are page-level links, won’t have the bottom line in the text section of the link – they won’t have any section title since they link to a whole page rather than a specific section of a page.

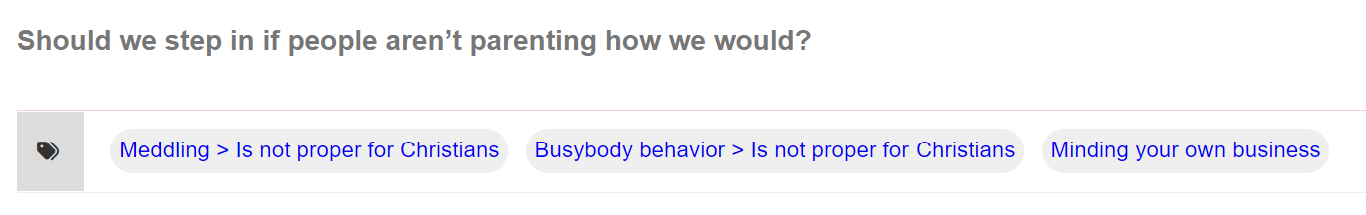

Bidirectional links: sections are tagged with their subjects

In addition to the subject index, the subjects are made readily discoverable by making the links bidirectional: each section on the page displays a list of its tags, with each linking back to the subject index.

Every section displays its own subject tags

That is to say, sections link to the subject index as well as the subject index linking to sections. This makes it easy to find related discussion for any specific topic with just a click or two. In my opinion, no other form of content cross-linking and categorization even comes close to the usability and convenience of this two-way per-section tagging system.

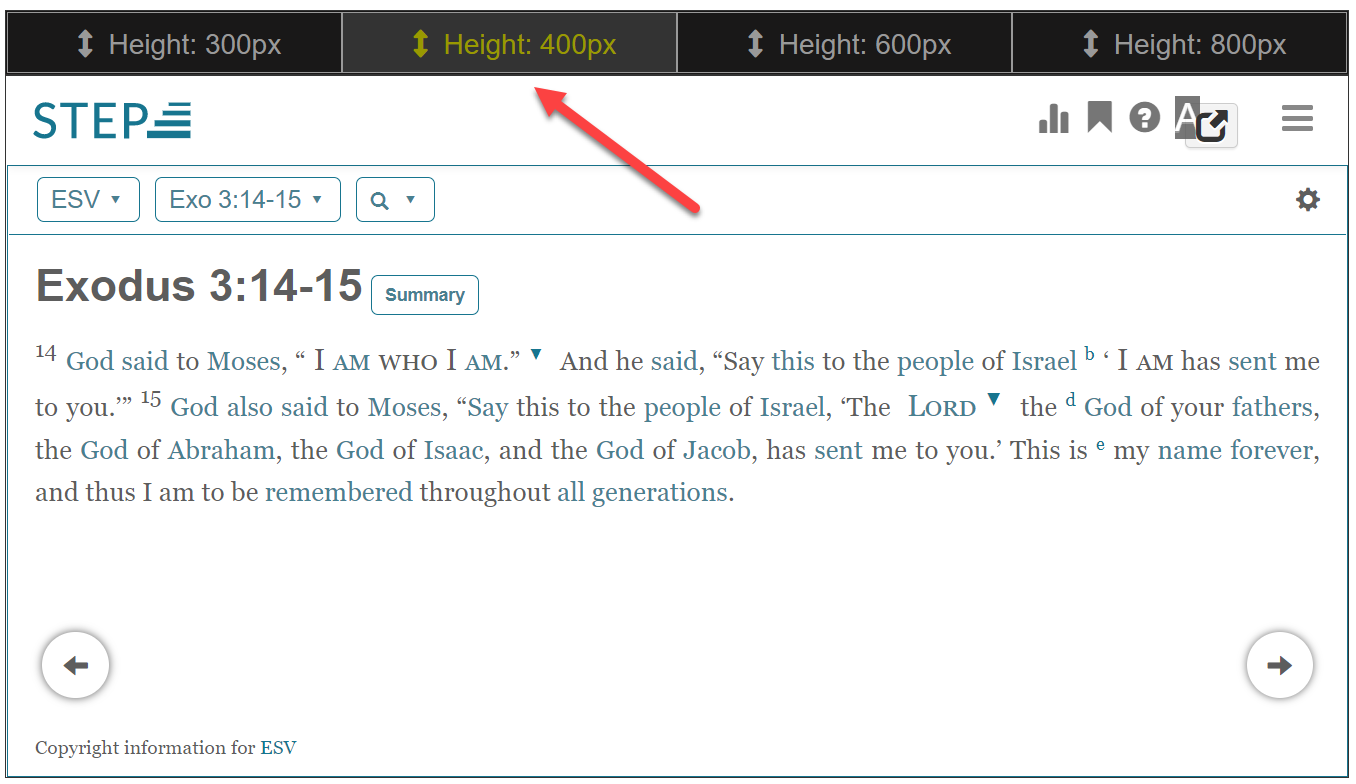

Embedded Bible app windows

This site embeds scripture in on-page windows from a Bible study application called the STEP Bible app. This free web app offers lots of useful functionality, but best of all, it can be seamlessly integrated into the writings on ministry websites using the programming interface that the developers of the application have kindly provided. This means you can leverage the features of the Bible study app directly from the pages on this site! I haven’t come across anything else similar in the time I’ve looked.

I have taken the liberty of adding a bit of extra interface to improve the user experience: you can select how tall the embedded windows are. In general, if you are doing anything more complicated (such as looking at cross-references or lexicon entries), you are probably going to want more height – perhaps even the full 800 pixels.

Above the embedded Bible app windows, you can select the height

Features the STEP Bible app offers

The embedded STEP Bible app windows offer lots of useful functionality for lay Christians. In roughly descending order of usefulness, in my opinion:

- Well thought-out cross-references (not an overwhelming quantity of them, but high-quality ones)

- An exhaustive original language concordance

- Parallel English versions

- A topical index that ties into scripture verse-by-verse (compare the Thompson Chain Reference system)

- Cross-linked Greek and Hebrew lexicons. For lay Christians, these are useful mostly just to be able to get a bit fuller view of the original language vocabulary behind the English, rather than going much further than that.

It is not a very good idea to draw grand sweeping conclusions from lexicons in a vacuum, that is, without an accompanying more complete understanding of Greek and Hebrew approaching the level of actual reading fluency. There is a lot more to “knowing the original languages” than simply looking at lexicons, and it is easy to make assumptions that aren’t necessarily valid if one has only a surface level of knowledge.

Lexicons and interlinears make it all too easy to overestimate one’s own knowledge, in other words. This doesn’t mean lay Christians can’t make use of such tools (such a rule would be blatant legalism), but it is just necessary to exercise caution in doing such, taking care to remember that God has called most Christians in the body of Christ to submit to pastor-teachers who have more knowledge than themselves.

It is a hard thing to accept (“Well, easy for you to say, Mr. Teacher, but what about me as a lay Christian?!”), but a necessary one. Humility is a critical part of what we might term “teachability.” And since God has seen fit for spiritual truth to come through pastor-teachers in this present age, being less teachable on account of resisting teachers’ authority – instead trying to do everything on your own (all the while lacking at least some of the requisite knowledge for going about things responsibly) – will necessarily lead to less spiritual growth, and perhaps a lot less at that.

If you are not a Bible teacher you can freely skip this section.

Teachers can go even a level deeper with the STEP Bible app. Aside from all of the above features, there is also additional more advanced functionality:

- Full grammatical parsing and morphology (available, for example, on the Translators Hebrew OT, Tyndale House Greek NT, and Rahlf’s LXX). Especially helpful for verbs and participles.

- Complete interlinears and reverse interlinears with many versions, including the ESV and NASB.

- Parallel versions with Greek and Hebrew: English alongside the original languages, multiple original language texts alongside each other (including both Hebrew and the LXX for OT passages), etc.

- Textual criticism resources (critical apparatuses, variant manuscripts like the Aleppo Codex and Samaritan Pentateuch, etc.)

All the permutations of the embedded Bible app windows used on this site

This list is exhaustive. Eventually, I will get around to coding support for dynamically toggling between all the possible options for a given New Testament or Old Testament passage. (The two kinds of passages are inherently different in terms of textual options, as the New Testament was written in Greek, but the Old Testament was largely written in Hebrew, with some Aramaic here and there).

New testament

ESV only

NASB only

A comparison between English versions: ESV, NASB, NIV, and HCSB

Tyndale House Greek New Testament

Interveleaved Tyndale House Greek New Testament and NASB

Old Testament

ESV only

NASB only

A comparison between English versions: ESV, NASB, NIV, and HCSB

Translators Hebrew Old Testament

Interveleaved Translators Hebrew Old Testament and NASB

Interleaved Rahlf’s Septuagint and Translators Hebrew Old Testament

Interleaved Rahlf’s Septuagint, Translators Hebrew Old Testament, and NASB

Automatic verse tagging in the Bible version of your choice

This site automatically tags scripture references in the Bible version of your choice, displaying them in a tooltip/pop-up. You can change which Bible version references will be displayed in on the settings page (e.g., NIV, ESV, NASB, NKJV, etc.). This is far from the only site to automatically tag Bible verses, but many do not make it possible to change the version, leaving you stuck with whatever the default is on their site (even if you’d rather use a different version).

You can also choose to have verses be tagged with a small L to the right of the reference, which will open the passage in Logos Bible Software. I have this off by default (to reduce visual clutter for all those for whom this is not relevant), but if you are a Logos user, this is very convenient.

All this is implemented with Reftagger, a nice free tool provided by the folks over at Faithlife. (The makers of Logos Bible Software – hence the integration).

Dynamic footnotes with hover behavior

Footnotes on this site use tooltips/pop-ups in much the same way as the verse tagging, to increase convenience. Using normal footnotes (that link down to the bottom of a page and force you to jump around everywhere) unnaturally breaks readers out of their reading flow. This is simply inconvenient and unnecessary. Using pop-up footnotes solves this problem.

You can see the footnotes on this site simply by hovering over them (or tapping them, if you are on mobile).

Here is an example footnote, 1 in the middle of a sentence.

Here is another footnote, 2 this one with a link. Being able to link to things in footnotes is absolutely critical, as one of the most frequent things footnotes get used for is citations.

Direct links to sources

Having written around a dozen lengthy formal papers across my two humanities majors in college (my two longest were a term paper for an 8000-level classics graduate seminar and a research paper funded by my University’s center for undergraduate research), I hate citations and bibliographical formatting with all the burning passion of 10,000 dying suns. No exaggeration. Both of the papers I linked above had multiple dozens of citations across their 30+ page lengths. I still recoil in remembrance of the hours I had to spend dealing with all this nonsense in those papers.

This notwithstanding, I am a huge proponent of intertextuality and rigor in writing, being meticulous in supporting all points wherever useful and beneficial. There are parts of academia I find positively intolerable (which parts led to me adding a third major in Computer Science and ending up a software engineer rather than a Classics professor), but the practiced skepticism of all assertions without evidence is not one of them. The scholar within me takes great pleasure in thoroughly-researched and well-supported writing, no matter what it is about. (Sometimes I even find it enjoyable to read excellently-done academic writing in fields I am not otherwise unduly interested in).

Unfortunately, paywalls cripple usable intertextuality in almost all of academia proper. Scummy for-profit publishing corporations keep human knowledge (even taxpayer-funded human knowledge) behind lock and key. For whatever inexplicable reason, lots of academics also seem hell-bent on keeping everything printed in dusty physical books rather than publishing resources on indexable computer networks. Having dealt with enough inter-library loans in my day – just to cite a paragraph or two accurately – I still get depressed at how much knowledge is made largely inaccessible for no particularly good reason.

At any rate, soapbox aside, I wanted a way to make referencing resources other than my own completely seamless – something instant, something with actually-good user experience. The internet supports general reference to pages and sections with hyperlinks and id attributes (on header tags, for example), but I want to be able to link directly to the paragraphs or even sentences I reference. Why not? It is technically possible, and has been for many years. So why in the world isn’t it done absolutely everywhere, since it is so superior?

While it is still mysterious to me why very few others implement these seemingly-obviously-superior direct sentence-level citation links, I can explain how I accomplish such in the materials of this site. This will be the focus of the next several sections.

Direct links to website quotes

Links to fine-grained content on public webpages are easy to accomplish via Google Chrome’s Text Fragments. If you want a deeper technical dive, you can have a look at the GitHub Repo and the main technical writeup:

- GoogleChromeLabs/link-to-text-fragment: Browser extension that allows for linking to arbitrary text fragments.

- Boldly link where no one has linked before: Text Fragments

Unfortunately, at the moment, text fragment links (deep links on webpages to specific text segments, like sentences) presently only work in Chromium based browsers – like Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge. The links simply do not work in Firefox or Safari, because those browsers have not yet chosen to implement the functionality. (Boo, hiss).

In practice, this means this functionality will only work if you view this site on Google Chrome or Microsoft Edge. Chrome has the largest browser market share by quite a lot, which is fortunate in this instance, but if you are one of the folks that uses Firefox or Safari, sorry but no dice. For this reason alone, I would recommend reading the materials of this site in Chrome or Edge.

This site uses these links very frequently for:

- Linking to specific things on Ichthys.com, the Bible teaching ministry run by my mentor and friend. This is probably the thing I use text fragment links for the most.

- Linking to public-domain or otherwise-freely-available reference resources on websites like StudyLight (technical commentaries and Bible dictionaries), Blue Letter Bible (lexicons), and others.

Direct links to published resources (like Bible dictionaries, lexicons, and so on)

While there is an incredible wealth of free reference resources, much of the scholarship is older. This actually tends to be advantageous in terms of the general outlook (there was more general scholastic conservatism and respect for the inspiration of the Bible in the past, particularly in pre-WWII scholarship), but there have been some important archeological discoveries (such as the Dead Sea Scrolls) and advancements in scholarship in some specific fields since then.

For this reason, it is often beneficial to turn to modern resources as well. Unfortunately, modern resources are still under copyright, which makes the above method of instant linking not workable, since it requires public webpages. For this reason, it becomes necessary to link to resources via Bible software programs. I use two programs to accomplish such: Logos and Olive Tree.

Logos and OliveTree

To my knowledge, Logos is the only Bible software program at the moment to support direct sentence-level resource links, and this advantage is absolutely massive. It is also the only of the three big players (Logos, Accordance, Olive Tree) to have a full webapp (letting you access your library from any computer, even without having any software installed), which is the usage I recommend for many or even most normal people, as it simplifies things. For these reasons, I own most of my reference resources in Logos.

There are a few resources that Logos doesn’t offer that I own in OliveTree. While OliveTree doesn’t really support resource hyperlinking, it does have an API for jumping to specific verses by hyperlink, which is at least better than nothing. It so happens that all of the resources I use and recommend for OliveTree are scrolled in-line with scripture, such that it is possible to reference them in this somewhat-roundabout way. What I mean by this will become clearer below.

How the direct resource links work

For easy identification, all links to resources external to Bible software are prefixed with a tilde (~).

As much as possible, I link to things in Bible study software (Logos and OliveTree) directly. As to things external to Bible software, non-webpage things that I can actually link (e.g., a PDF of something on Archive.org), I do. Otherwise, the link is where to purchase the resource (or at least one option for such – I generally prioritize Amazon links). Any true web resources are linked the text fragment way, as described above.

I create the link text for different resource links a bit differently, so give pertinent examples of all the types here. All resources (both those linked in Bible software and those linked external to it) obey these rules. So, for example, reference works external to Bible software programs are linked in essentially the same way as those that are in them – that is, sometimes by section name, and sometimes by page number.

You can see the full list of resources I use and quote from in the site’s resource index. Note that I use resource abbreviations (or at least partial abbreviations) quite frequently; these abbreviations are defined in this index.

Biblical texts

The links are constructed as {Text} > {Verse}.

I create link text for biblical texts all the same way, be they English Bible versions or Greek or Hebrew texts.

Examples:

Lexicons

The links are constructed as {Lexicon} > {Lemma}.

Examples:

In-line resources: study Bibles, Bible handbooks

The links are constructed as {In-line Resource} > {Verse}.

The main in-line resources I use (the NIV Study Bible, a couple Bible handbooks) are OliveTree resources, meaning direct links are not possible; the best I can do is link to a specific verse, which will navigate you to that verse in your Bible in OliveTree. You can then open the in-line resource, which will automatically sync to the verse’s location. This is a bit indirect, but it actually adds very little time in practice.

Examples:

- NIV Study Bible > Romans 8:28

- Unger’s Bible Handbook > Micah 6:8

- Halley’s Bible Handbook > Philippians 4:13

In-line resources: topical resources

The links are constructed as {In-line Topical Resource} > {Verse} > {Topic}.

These are OliveTree resources too. Generally, what it is desirable to link to is the verse listing for a specific topic. Unfortunately, since OliveTree does not support full content hyperlinks, this is not possible to do directly.

However, we can do this indirectly, similar to how we got to the in-line resources indirectly above. We just have one more step here: once you arrive at a specific verse in an in-line topical resource, you’ll need to click on the appropriate topic to jump to the full verse listing for that topic. This adds a couple seconds, but it is still really not all that inconvenient. In the future, if OliveTree ever gets support for full resource hyperlinks, even this slight inconvenience could be eliminated.

Examples:

- Thompson Chain Reference > John 3:16 > 2206 God’s Love

- Dictionary of Bible Themes > Romans 3:23 > sin, universality 6023

- Olive Tree Bible Topic Threads > Ephesians 2:8 > Grace

Commentaries

The links are constructed as {Commentary} > {Verse}.

The commentaries I favor most are Unger’s Commentary on the Old Testament and the verse-by-verse study videos put out by Bible Academy, but I do also occasionally link to some technical language commentaries as well.

Examples:

- ~Unger’s OT Commentary > Genesis 1:2

- ~Bible Academy > John 1:1

- Meyer’s Commentary > 1 Corinthians 4:6

- Keil and Delitzsch > Isaiah 5:1

Bible dictionaries and encyclopedias

The links are constructed as {Dictionary/Encyclopedia} > {Topic}.

Examples:

Digital reference works

The links are constructed as {Reference Work} > {Section} (if a specific section is in view) or {Reference Work} > {Location} (if the link is to a specific volume/page).

These sorts of links encompass more general reference works that aren’t organized by verse or topic – books, in other words. Works on systematic theology, church history, and so forth are thus linked in this way.

Examples:

- Chafer’s Systematic Theology > The Divine Program of the Ages

- Schaff’s Church History > Volume 7, Page 98

- Walker’s Church History > Page 57

-

The body text of the footnote. ↩︎

-

Dynamic footnotes with hover behavior: A section explaining how footnotes work on this site. ↩︎